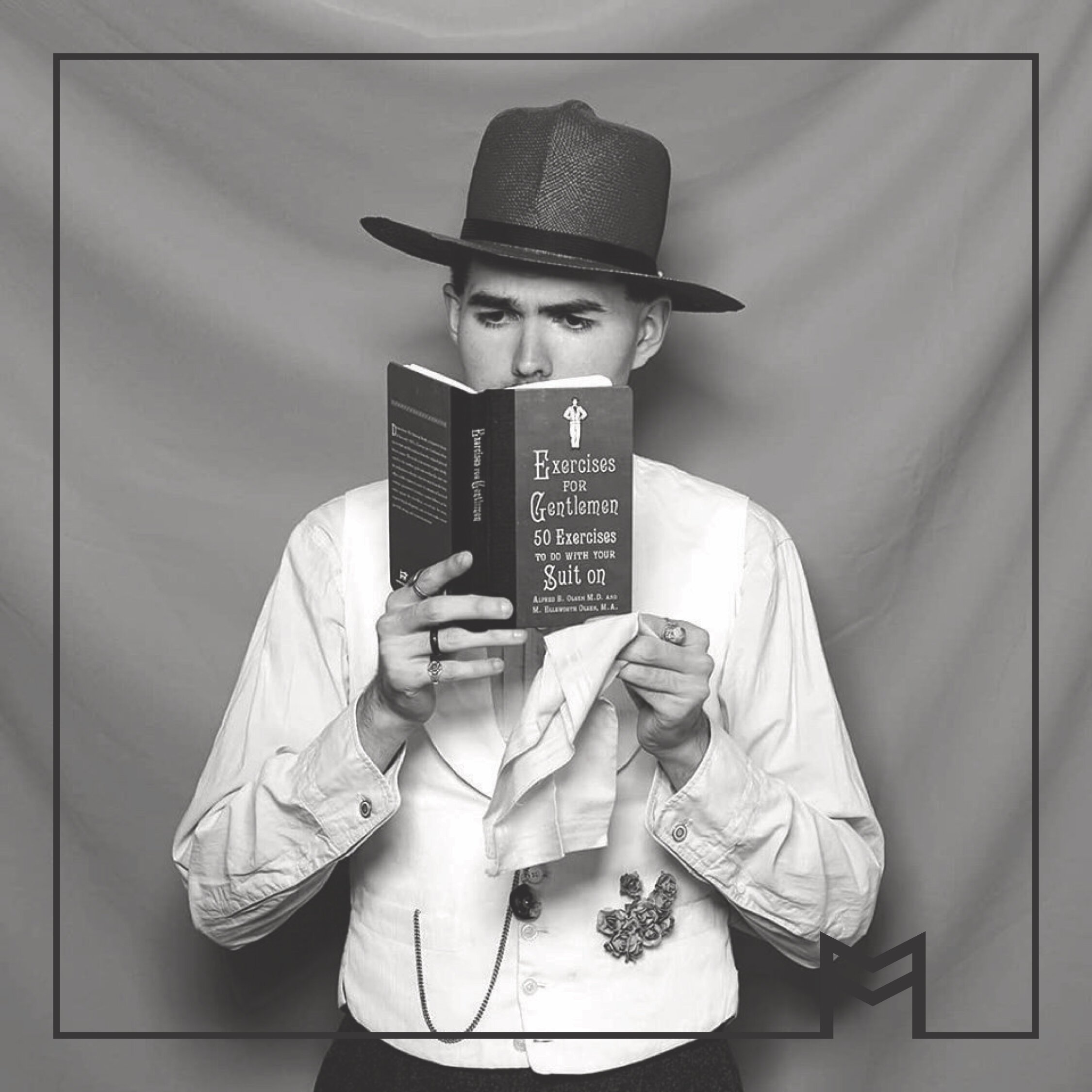

Please join us in The Exhibition Space for BEAST, a solo exhibition by Adelaide/London based artist Lucas Croall.

The Mill is excited to present this new body of work by Adelaide ex-pat and former The Mill resident Lucas Croall. BEAST takes the form of a series of prints presented alongside the plates used for their creation. The content of the exhibition seeks not only to consider the themes of the artist’s work but also to offer insight into the medium of printmaking.

‘BEAST investigates notions surrounding the tension between civilisation and wildness. By putting particular focus on the impossible demands that civility places on the human animal, the work seeks to highlight the familiarity of life’s most troublesome beasts.’

Artists biography:

Lucas Croall is an artist who specialises in Printmaking, and has a background in Interior Mural works. Lucas graduated with a Bachelor of Visual Arts at The University of South Australia in 2015 and completed his Masters at the Royal College of Art in London in 2019. He is also a curator, and has curated a number of art shows in galleries in Adelaide, Melbourne and London. Lucas’ printmaking works have been exhibited in numerous solo and group shows. In 2018, his work was selected by Grayson Perry to be exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts 250th Summer Exhibition in London.

He has designed and painted interior murals in Adelaide, Sydney, Melbourne, Barcelona and London.

Lucas Croall’s prints and installations investigate notions surrounding the tensions between civilisation and wildness. His images often depict mutated animals or humans and aim to realise states of the psyche. By putting particular focus on the relationship between public presentation and private life, his work examines these themes through social criticism and evaluations of modern psychology.

Artist statement:

BEAST

During the late stages of construction of London’s tallest building (the Shard), staff discovered an animal living on the 72nd floor of the tower. It was believed that a fox had entered the site through a central stairwell and was surviving off of food scraps left by construction workers.

Traditionally most foxes have lived in rural areas, in a series of underground tunnels referred to as dens. Recently numbers of urban foxes have increased, mimicking human migration from the country to the cities. One reason for this migratory pattern in foxes may be due to a lack of food in the countryside and an increasing tendency to scavenge. Generally, a fox’s territory in the countryside can range up to 40 miles, and with the exponential growth of cities and the large areas a rural fox would ordinarily cover, it is easy to see how the two have become enmeshed.

The fox in the Shard represents a humorous anomaly for the British media but underneath this example belies the fox’s characteristics for survival in precarious urban areas. In this case upon discovery of the fox, the animal was removed by Southwark Pest Control, fed and given a health check before being released onto the streets of Bermondsey (not far from the tower). To this date the Shard remains the tallest building in Western Europe.

*

The tenuous nature of certain forms of wildlife in their encounter with the domestic world of human beings is connected to the elusive associations that surround our distinction between wildness and civilisation. The contemporary connotations of rudeness are impropriety and lacking manners. The Latin root of rude is rudis which means ‘unwrought’ (referring to handicraft), and figuratively ‘uncultivated’. Rudis is a cognate with rudus meaning broken stone, debris, or lump (especially that of bronze). Here the Latin root of the word rude becomes suggestive of the Bronze Age. In terms of civilisation then, ‘rudeness’ would become suggestive of something uncultivated and rough but also that of an early civilisation.

Enlightenment thinker Adam Ferguson, in Essay on The History of Civil Society, argues that what withholds civility from falling back into ‘rudeness’, or in other places he calls that which is ‘savage’ and ‘bestial’, is the fact that civility is built up through progress. He generously states that early ‘inhabitants of Britain’ were akin to ‘the present natives of North America: They were ignorant of agriculture; they painted their bodies and used for clothing the skins of beasts.’ For Ferguson those who wear the skin of the beast has a clear demarcating role in showing who is and who is not civilised.

Ferguson’s separation of civility and rudeness, arguably, is a false one. Looking at Ferguson’s example of a time when people in Britain ‘used for clothing the skin of the beast’ this is easily proved as inaccurate as we still today make use of material to wear from what Ferguson might call the ‘beast’. This can be seen in particular in the form of leather.

*

Jacques Derrida, in his series of seminars, The Beast & The Sovereign, insists not on the proposition of an opposed dichotomy between what is unwrought and what is civil, but on a grace found in the recognition of each existing within the other. The beast is the sovereign, and sovereignty is found in wildness. One distinctive feature of deconstructionism is its insistence on the maintenance of that awareness, and the interrogation of mental separations between animality and what is anthropocentric. Derrida says that the process of deconstructing the relation between animality and sovereignty is a key theme of the deconstructive process in that understanding this demarcation or threshold between the pair shows how structures of the state and nation-state operate and how logic, reason and progress are thought. Derrida states in the third seminar of Vol. I that deconstruction is a rationalism without debt, that is unconditional, and that requires it to be ongoing, therefore enlivening rather than taking stable meanings in dichotomies.

This may seem an interminable task, however, Derrida gives deconstruction a limit. This limit is found at the threshold. He states that the ‘threshold [is] at the origin of responsibility, the threshold from which one passes from reaction to response, and therefore to responsibility… the indivisible limit between animal and man.’ The question is of locating the threshold, the limit, the demarcation, between civility and rudeness, between the beast and the sovereign.

PRINTMAKING

The confrontation of the beast and the sovereign within the tradition of printmaking is seen in the tension between the limited edition and unlimited reproduction. As a response to the privileging of authenticity in art history, printmaking employed the limited edition as a means of securing its status as a sovereign medium. This practice also seeks to rescue the medium from falling into the spectral practice of commoditization. Reproducibility and authenticity rise up in relation to each other and have a tendency to reify the other’s legitimacy.

Hito Steyerl, in her essay, In Defence of The Poor Image, elucidates the contemporary promise of new media, namely their ability to constitute dispersed audiences while it disseminates images. The beast of printmaking rears its head in the form of reproducibility, pushing at the threshold of authenticity and spilling over into accessibility.

Printmaking exists as an antagonism. It simultaneously makes a promise as a democratising agent and threatens to seal itself off as a limited edition. In the context of the BEAST exhibition, the image is dispersed in a myriad of iterations, but its numbers are fixed in edition numbers, positioning the BEAST on both sides of the antagonism.